Researchers are turning soil sounds into songs

When David Attenborough said saving the planet is now a communications challenge, he probably wasn’t thinking about the possibility of DJs doing soil sets.

Like many others, David knew that half the battle of saving the world is getting people to engage with green solutions and technology – and scientists at UWE Bristol are planning to do just that by turning their research into music.

Dr Sam Bonnett is a senior lecturer of environmental science at UWE Bristol and has been studying soil ecology for 20 years. But Sam doesn’t just look at soil, he now listens to it too. You could say he has his ear to the ground.

Termed soil ‘eco-acoustics’, the novel field of listening to soil could tell researchers a wealth of information, including the soil’s geo-physical makeup and how biodiverse and healthy it is. The healthier the soil, the more diverse a range of noises you can hear when you put a microphone to it.

To some this may seem trivial, but soil is at the forefront of climate conversations for good reason. Globally, agriculture makes up about 25 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions, which is more than from the transport sector.

Farming soil has historically released the carbon that it holds into the atmosphere for one, and intensive farming reduces soil health which makes growing food less efficient. Bad soil health means more land is needed to grow the same amount of food, which in turn has a negative impact on biodiversity.

Dr Bonnett foresees that in 10 years’ time farmers could have eco-acoustic monitoring stations around their land connected to an app to tell them how healthy their soil is. Such monitoring stations would be cost effective and easy to set up compared to current monitoring approaches, thus the roll-out potential is significant.

Together with colleague Dr Adrian Crew, Dr Bonnett will publish a paper later this year about how soil carbon could be monitored using sensors and acoustics. This could be hugely influential in deciding which land to farm and which land might need management or restoration and assist farmers to evidence their sustainability achievements.

Such widely applicable research will require widespread public support if it is to make an impact. To this end, Dr Bonnett thinks that one of his students might have the answer. Pioneering the crossover between soil science and music is Robbie Sidhu, who is studying for a Masters of Research at UWE Bristol.

Robbie has begun turning the soil sounds the team are surfacing into music which he’s releasing on YouTube. The first piece, soundsystem soil 001, has a distinctly Bristol drum and bass sound.

It leads one to think, how inspired would festival goers be to invest in the soil beneath their feet if they could hear it live as part of a show?

Successful tunes could even directly raise funds for nature restoring projects. In April this year, a collaboration between the Museum for the United Nations and UN Live set up ‘NATURE’ as an artist on Spotify through the ‘Sounds Right’ project. Anyone listening to NATURE, who has already collaborated with the likes of David Bowie, Ellie Goulding and London Grammar, will be generating royalties going directly to conservation projects. ‘Sounds Right’ is projected to raise more than $40 million in its first four years.

Dr Bonnett and his students at UWE Bristol are setting up eco-acoustic monitoring stations around campus to gather data on urban soundscape ecology. The stations will also monitor water sounds and air sounds for reference against soil acoustics.

“I like to use the analogy of Stranger Things and the Upside Down”, said Dr Bonnett. “There’s a whole world beneath our feet which is right there with you all the time but you don’t know about it.

“We don’t know yet what the answer is to sustainable farming. It could be rewilding land, or it could be vertical faming and aquaponics – but both of those things are still going to need the soil monitored to see what impact is being had.

“Soil can help us store carbon, it can help us grow healthy and nutritious crops and who knows, maybe it can make great music too.”

Five years from now, you could be listening to The Beatles featuring beetles on your morning commute, or perhaps a bit of De La Soil.

Related news

15 December 2025

UWE Bristol rises eleven places in People & Planet University League

UWE Bristol has risen to 14th in the People & Planet University League (UK), a jump of eleven places.

12 December 2025

UWE Bristol’s environmentally conscious and student-focused accommodation wins three awards

Purdown View, the world's largest certified Passivhaus student accommodation development, has been recognised at Property Week Student Accommodation Awards.

20 November 2025

UWE Bristol ranked among top 12 per cent of universities globally for sustainability

UWE Bristol has climbed over 400 places in the QS World University Sustainability Rankings 2026, which evaluates universities on a range of environmental and social impacts.

06 November 2025

UWE Bristol welcomes West of England Mayor for annual Green Week

Helen Godwin, Mayor of the West of England, visited UWE Bristol during its annual Green Week to see the sustainability-driven research, innovation and skills initiatives that are helping to power the growth of the region’s green economy.

16 October 2025

UWE Bristol signs Repair and Reuse Declaration in commitment to sustainable initiatives

UWE Bristol is the first UK university to sign the Repair and Reuse Declaration as a whole institution, a call to legislators and decision makers to tackle climate change through greater repair and reuse support.

15 October 2025

UK food needs radical transformation on scale not seen since Second World War, new report finds

A new report from the Agri-Food for Net Zero Network+ finds urgent action on food is needed if the UK is to reboot its flagging economy, save the NHS billions, ensure national food security, and meet climate commitments.

24 September 2025

UWE Bristol to help protect threatened forest in Madagascar in £800k project

UWE Bristol is a partner in a groundbreaking project awarded almost £800,000 in funding to protect one of Madagascar’s most precious and threatened forests.

24 February 2025

WESTbusStop+ makes sustainable travel more convenient

A new WESTbusStop+ bringing together buses and other ways to travel has been officially opened at UWE Bristol’s Frenchay campus.

03 January 2025

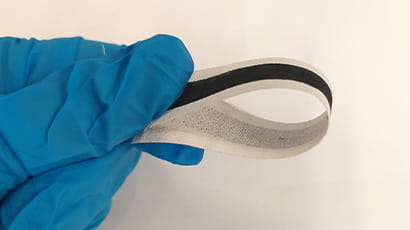

Big leap forward for environmentally friendly ‘e-textiles’ technology

Research led by UWE Bristol and the University of Southampton has shown wearable electronic textiles (e-textiles) can be both sustainable and biodegradable.

28 November 2024

Work of UWE Bristol academics features in Government report on air quality measurement

Two UWE Bristol academics have made contributions to an influential Government report on the measurement of air pollution.

27 November 2024

Traffic noise reduces the stress-relieving benefits of listening to nature, study finds

Road traffic noise reduces the wellbeing benefits associated with spending time listening to nature, researchers have discovered.

15 November 2024

Grasslands project led by UWE Bristol academic to support UK’s bid for net zero emissions

A UWE Bristol researcher will lead a £4.7 million project focused on the management of UK’s grasslands aimed at supporting efforts to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

You may also be interested in

Media enquiries

Enquiries related to news releases and press and contacts for the media team.

Find an expert

Media contacts are invited to check out the vast range of subjects where UWE Bristol can offer up expert commentary.